1:30min

Photo: Freedom Scientific

______________________________

By Paul Graveson

BOptom BA GradCert(Optom) PGCOT

Optometrist, Low Vision Consultant

As optometrists, most of our measurements of vision use high contrast. We use high contrast letters on our distance acuity charts, and we ask our patients to read near charts which are black print on nice white background; however, when eyes are affected by pathology, high contrast vision may be the last function to be affected.

We can use this to our advantage. By giving the low vision patient higher contrast text, we can often make a big improvement in their comfort and fluency of reading.

One important technical note: getting more illumination on the page does not improve text contrast. Sure, it looks like it does: the white background looks whiter and the black text looks blacker, but even though the white page is brighter, the black text is brighter too.

Text looks black because the ink has a much lower reflectance than the paper. For instance, consider a page with paper reflectance of 90 per cent and text reflectance of only 10 per cent. The contrast is 80 per cent, whether in a dim room or in bright sunlight, but under the bright sunlight the black text might actually be reflecting more total light than the white paper had been in the dim room. The blackness and whiteness are relative; text looks more ‘contrasty’ under brighter light simply because that’s how our retinas function best.

When we consider screen-based equipment, the situation is a little different. The brightness of the text relative to the background is not the only factor. Whether it’s a computer, a tablet, a smartphone or a CCTV, the contrast is also affected by the amount of veiling glare (reflections off the screen surface). Being in very bright light can make the display invisible, even to those of us with normal vision. It’s important to make sure the screen is kept clean, and take care to position it to minimise reflections of windows and lights off the screen. It helps to boost the brightness of the display itself, but using stronger ambient or task lighting only makes the reflections worse.

Measuring contrast impairment

Almost all low vision patients have impaired low contrast vision. Measuring contrast impairment is easy with a logMAR high/low contrast reading chart. Dr Alan Johnston produced a chart some years ago which has been circulated widely in Australia. It’s really two logMAR charts in one: one is high contrast black print, one is very low contrast light grey print. Simply measure the smallest print they can read on each side. If the grey print is more than three lines worse, they have a contrast sensitivity function problem. If it’s more than six lines worse, their problem is very significant. With AMD, many patients won’t be able to read anything at all on the grey side, even if they read down to N4 on the black; to them, anything with such low contrast is completely invisible.

This is a good time to pause and discuss the result with the patient. You might be the first person to really understand the patient’s problem. If previous practitioners have tested only high contrast vision, the patient may have been told their vision is still quite good. Even though that sounds like good news, patients are often confused and frustrated, because they don’t feel their vision is very good at all. Low contrast acuity is a much fairer reflection of quality of vision, and a better correlation with real world function.

In many low vision conditions (most especially AMD), vision often appears a bit like a badly exposed photo in which all the richness, subtlety and texture of the image have dropped out. Patients may have problems with seeing faces, reading newspapers, and detecting the edges of gutters and stairs. Because it’s only subtle shadowing that reveals the contours of lawns, dirt paths and uneven pavements, they often have an increased risk of falls.

Ask the patient if they’ve experienced those problems. For the patient who has been struggling with understanding the nature of their vision loss, having their experience validated by an expert that ‘gets’ their problem is often powerful.

Photo: Freedom Scientific

Improving contrast

The first thing you should do is make sure they have the best task lighting possible. That sounds like I have just contradicted what I said above. It’s true, contrast is a property of the document itself and doesn’t improve with increased illumination; however, pretty much everyone who has a contrast function deficit has a luminance function deficit as well, so make sure illumination is sorted out straight away.

Technically, it’s pretty much impossible to increase document contrast. Yellow filters can improve it a little for some patients, but at the expense of reducing brightness of the image. When contrast is a problem, the most effective answer is substitution, that is, replacing the low contrast document with a high contrast presentation of the same information. All the best substitutes are screen-based electronic devices.

An obvious example is viewing a newspaper’s website (on a computer or tablet) instead of reading the printed newspaper. Newsprint has notoriously poor contrast. Most patients will complain that it’s much worse than it used to be, but the patient’s eyes have changed, not the newsprint. Newspaper websites have much better contrast, but if more improvement is needed then a great strength of electronic displays is that contrast can be optimised further. Both Windows and Mac computers have contrast customisation options built into their accessibility controls, as do most smartphones and tablets. Instructions for specific systems can be easily found online by searching for ‘accessibility’ and the system/device.

Similarly, banking online is much easier to see than using a magnifier on a paper bank statement. Most household bills can be received by email and viewed on screen, and patients can avoid the tiny print used in stock market reports and sports results by viewing them on websites instead.

For reading novels, an eReader app on a tablet is much more versatile than a physical book. Tablets can be set to display high contrast print, which can also be made brighter and larger as needed. Unlike book print under an optical magnifier, very large print on tablets can still be read fluently because the print reconfigures itself to fit on the page; the pages need to be turned more frequently, but there is no need to scroll or navigate across the line. Bigger screens are better, but good fluency can be achieved even with very large print on smartphones.

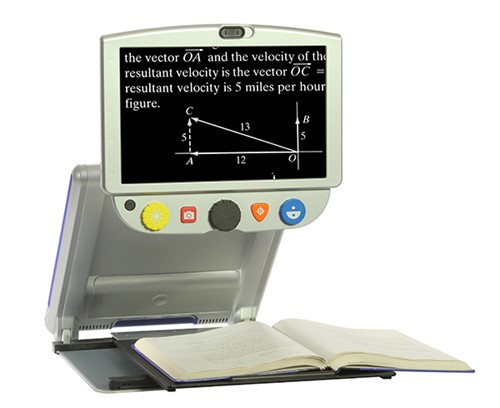

When paper documents cannot be substituted by electronic means, a CCTV is called for. Modern CCTVs have wide screens and high definition cameras, along with enhanced contrast display modes. The excellent image quality and wide field of view make them ideal for working through longer documents for prolonged periods, even at higher levels of magnification. Even patients with relatively early low vision can benefit from a CCTV, as it lets them remain efficient at work and continue to enjoy pastimes such as reading books and doing puzzles.

READ

LOW VISION: Part 1. Understanding

LOW VISION: Part 2. Illumination

LOW VISION: Part 3. Magnification

LOW VISION: Part 5. Choosing aids

LOW VISION: Part 6. More about aids

______________________________

This series of articles has been prepared with the support of the Tasmanian Optometric Foundation. Contact Paul Graveson at admin@hobartoptometry.com.au.