1:30min

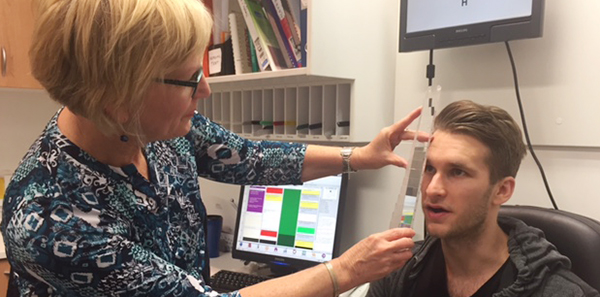

Liz Wason with Luke

______________________________

By Liz Wason

DipAppSc(Optom) GradCertOcTherap FACBO

Leederville WA

Case study

Luke was referred by the State Head Injury Unit for a neuro-optometric assessment and care in relation to ongoing and persistent visual symptoms, as a result of a severe concussion injury while playing rugby.

The injury was a blunt trauma of a high-speed knee collision to the front of his head causing rotational force and a contrecoup injury as the back of his head contacted the ground. Luke was at that time an intelligent 26-year-old law student who was extremely fit and healthy.

He reported at the time of the incident loss of consciousness for about one to two minutes, followed by significant disorientation, nausea, memory lapses, slightly impaired speech responses, and severe headache and balance issues for about one week.

Many of these symptoms have continued in varying degrees for the past six months since his injury despite intensive medical care, medications and intervention therapy including occupational, psychological and physiotherapy. As often is the case, various repeated medical imaging (MRI and CT scan) did not display any specific brain lesions.

His presenting complaints at vision assessment included severe headaches, poor concentration and attention skills, blurred distance vision, poor depth perception for driving, disorientation and reduced confidence for mobility, and hypersensitivity to light and noise.

As a consequence, he was no longer attending university, he was not able to read and process information, he could not comprehend movie story-lines, he avoided driving and social environments, he could not perform high-level exercise and was suffering depression. Obviously his life had drastically changed even though he was a determined person.

My examination confirmed myopia (R & L -1.00 sph), which he reported pre-head injury, but with a mild -0.25 increase from his previous spectacles. Focusing skills for near tasks were poorly sustained with + 1.25 lag of accommodation, difficulty changing focus, and remote blur point for small print at near.

His binocular vision skills were unstable with moderate exophoria and low base out fusion ranges at near. Intermittent diplopia was reported in all areas of gaze when fixating a target for pursuits, displaying cog-wheeling and vergence break-down requiring effort and excessive attention to regain fusion.

All structures for both anterior and posterior eye were normal with no optic neuropathy. Pupil reactions were equal and reactive.

Visual fields results (24-2) displayed no significant field loss but showed scattered scotomata of reduced sensitivity for both eyes, and with a small superior defect left eye which may be directly related to head trauma location.

In my experience, post-concussion syndrome presents with consistent visual components as reported by Luke. These include difficulties of:

- Visual spatial awareness, causing disorientation, impaired balance and movement stability, reduced depth perception impacting driving and navigating stairs, and reduced confidence in busy environments

- Focusing dysfunctions, causing poor visual attention for sustained tasks including reading, computer, sport, driving, conversation and movies. Myopia often occurs through poor focusing flexibility

- Dysfunctions of eye movement control, affecting reading and writing fluency, scanning for driving, sports and mobility outdoors

- Binocular vision instability, causing reduced attention for any visual task, irregular fluency for reading, copying and writing ,intermittent diplopia, poor depth perception and judgement for distance or near activities

- Photosensitivity and heightened glare symptoms associated with sunlight, artificial lighting, contrast patterns and flicker, often causing motion sickness

- Visual processing skills issues, causing difficulty using visual and other sensory information sequentially, rapidly and effectively.

Concussion can vary in magnitude but often in moderate to severe cases will impact the visual system. Any head injury which results in even brief loss of consciousness is classified as at least a moderate brain injury.

Concussion often does not present with evidence of structural damage in medical imaging but is known to initiate an irregular metabolic response in the brain, as well as possible axonal shearing in the mid-brain or brainstem. These changes impact on many functions affecting activities of daily living, and processing and interaction in the visual- vestibular- somatic complementary systems.

In Luke’s case, treatment included near spectacles for reading and study, with lenses with low power prism and light tint due to his photophobia and migraine-type headaches. Discussion also centred on using his distance photochromic spectacles more often to improve acuity, reduce glare and eyestrain, stabilise spatial skills and improve confidence in mobility.

Vision therapy is to be commenced in the near future to improve the diagnosed dysfunctions of accommodation, vergence and eye movements.

Counselling and advice is also a key aspect of our role. Providing reassurance is beneficial and acknowledgement that these symptoms are common, and can improve with care from an appropriate intervention team of which optometry is an integral member.

Consequently communication with all medical team members and conducting regular reviews is essential. However, setting realistic goals for progress is an important conversation with the patient, as well as encouragement to continue all recommended treatments as part of an overall care plan.

1. Ciuffreda KJ. The scientific basis for and efficacy of optometric vision therapy in non-strabismic accommodative and vergence disorders. Optometry 2002; 73: 735-762.

2. Scheiman M, Wick B. Binocular and accommodative problems associated with acquired brain injury. In: Clinical Management of Binocular Vision: Heterophoric, Accommodative and Eye Movement Disorders 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2002: 573-595.

3. Leslie S. Accommodation in acquired brain injury. In: Suchoff IB, Ciuffreda KJ, Kapoor N eds. Visual and Vestibular Consequences of Acquired Brain Injury. Santa Ana: Optometric Extension Program Foundation Press, 2001. 56-76.

4. Ciuffreda K, Ludlam D, Yadav N. Does vision therapy work? The wrong question: a perspective. Vision Dev Rehab 2016; 2: 2: 101-104.

A comprehensive list of further references relating to accommodation and vergence dysfunction in acquired brain injury is available on request.