1:30min

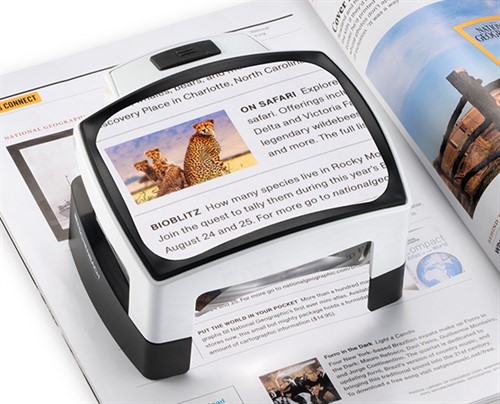

Photo: Eschenbach Optik GmbH

______________________________

By Paul Graveson

BOptom BA GradCert(Optom) PGCOT

Optometrist, Low Vision Consultant

Paul Graveson continues his series on the fundamentals of low vision practice with practical advice on magnification.

______________________________

When most people think of low vision, they think of magnifiers. In my previous article I explained why I believe that illumination is the best parameter to modify first, but illumination will take you only so far. When it’s not enough, it’s time to introduce magnification.

Magnification sounds simple but it can be challenging to prescribe properly. Illumination has just one significant limiting factor (glare), but almost every magnification device has several. Some are due to the physical designs of the magnifiers, but some are inherent in the phenomenon of magnification itself. It’s of utmost importance that the magnifier is matched not just to the target print size, but also to the specific type of reading task and the patient’s own physical and cognitive limitations.

The main drawback is reduced field of view. Stronger lenses are impossible to make in very large sizes, so the aperture becomes smaller as the power increases, which quickly becomes a limit to fluency and reading comfort. To compensate, patients need to hold the magnifier closer. I describe this to patients as the ‘porthole principle’. To see a wide view of the ocean through a porthole, you have to come closer to it. The optics of stronger magnifiers are designed for use close to the eye. If they are used at a normal 40 cm reading distance, the periphery looks distorted, further constricting the field of view. When introducing a patient to stronger magnifiers, you’ll find you have to keep prompting them to hold it closer.

At the same time as the lens aperture is getting smaller, the image of the document itself is becoming larger. An A4 page magnified by 6x creates an image taller than most patients. Because you can see only a small part of the image at one time, it can be tricky to navigate around a page to find what you want to see, especially for documents such as bills or bank statements. As you move across the image, the image of the text appears to flow back the other way, which can be disorientating or even cause motion sickness.

Hand tremors make the image jump around or go out of focus when using hand-held magnifiers, especially with stronger powers. Stand magnifiers are steadier because they rest on the page, but they can be hard to smoothly slide across the midline and edges of magazines and books. Non-illuminated magnifiers may cast shadows over the text, reducing the image quality.

Taken together, I think of these factors as imposing a ‘speed limit’, which can make a mockery of even the best formulae for predicting reading speed. No matter how visible they make the text, not all magnifiers have potential to allow fast fluent reading. It’s easy to verify, just by using the magnifiers yourself. For instance, I read a page of 375 words in one minute. Using a simple hand-held magnifying glass (+5.00 D 80 mm diameter), my reading speed drops, but is still a fluent 250 wpm. On the other hand, with a 10x (+40 D) illuminated stand magnifier I can’t read faster than 93 wpm. I have perfectly good vision, so if that is as fast as I can go, I can’t expect my low vision patients to go any faster, no matter what the formulae say.

Does that mean a slow magnifier isn’t any use? Not at all, but we have to consider: how fast does the patient need to read?

When patients say they want to read, often what they mean is reading a book, in which they become immersed in the story. Immersion generally requires a speed of at least 200 wpm. This is possible with some magnifiers but not all. It’s important to be aware that full-speed reading out loud can still be a lot slower than the patient’s silent reading speed. I read out loud at only 200 wpm compared with silent reading speed of 375 wpm, so even if a patient seems perfectly fluent reading a passage with a magnifier, they might still be a long way below their accustomed fluency.

Below high fluent reading is reading for information. A notification from the bank, the births and deaths section of the newspaper, or a letter from a friend does not require immersive fluency, but too slow can still be frustrating. Reading at least 90 wpm should be sufficient.

Then there is spot reading. For a price tag, a recipe, the television guide, or the power bill: anything above 40 wpm should do. A patient who is determined to be independent can do well at even slower speeds. Being able to read at least slowly is a lot better than not being able to read at all, and it can make the difference between staying independent and being helpless.

We run into trouble when expectations aren’t clear. When we demonstrate a magnifier that gets a patient reading the Yellow Pages slowly and they say ‘But I can’t read like that!’ it’s a clue that we need to clarify what their goals are. It’s often useful to ask patients if they used to be big readers. If they never used to read novels before their vision loss, they’re unlikely to want to start now and they will be quite happy with slower magnifiers. Even patients who really want to read books might also find slower magnifiers the best choice for other activities. For instance, a small pocket magnifier might be the perfect solution for looking at price tags in the shops, and shouldn’t be rejected just because it isn’t also suitable for reading novels. Many patients require more than one magnifier.

Another thing to consider is how much effort it takes to use the magnifier, compared to how much stamina the patient has. Some magnifiers are heavy or unwieldy, so they might be very effective but are also fatiguing. Some patients have little arm strength and cannot use even lightweight magnifiers for long. Stand magnifiers mostly need a supporting surface under the document, which means sitting at a desk or table. The posture needed to see into the stand magnifier can be uncomfortable, even with the help of a reading stand, and most magnifiers need at least one hand to hold them, leaving only one to hold the book.

No matter how good the magnifier, if the patient can’t hold everything in alignment for long then extended periods of reading will be impossible. Supports such as reading stands, lap tables or cushions on the lap can help, but sometimes patients just have to break their reading task into many short sessions over the day.

Photo: Eschenbach Optik GmbH

Will magnification help this patient?

The traditional starting point for trialling low vision aids is to measure the patient’s current near acuity, determine the target text size, and then calculate the amount of magnification they will need. While you’re at it, you can verify whether magnification will help.

Let’s say your patient can currently read N12 slowly on a well-illuminated chart. Ask them to read the N24 text on the chart as well, which is exactly the same as giving them a perfect 2x magnifier. Twice as large is the same as three lines reserve on a logMAR chart, which should mean a substantial improvement in fluency and comfort.

If you get that improvement, well and good: go ahead with trying magnifiers; however, some patients might not read much better, or even be worse, which can be confusing and dispiriting for both patient and optometrist. It’s an important finding though. It implies that their reading performance is limited by factors other than the size of the print.

Usually that means field loss just near the fovea, such as in AMD (wet or dry), or a right macular hemianopia, or inaccuracy of saccades (such as in Parkinson’s disease). If reading actually gets worse with larger text, they might have a ring scotoma (a small central island of foveal vision surrounded by dense field loss), a common situation with dry AMD (geographic atrophy). Whatever the cause, if simply giving much larger print doesn’t improve reading comfort, there’s little point using magnifiers to achieve the same thing. That time would be better spent looking at illumination or contrast options, or arranging referral to a low vision clinic.

If you’re lucky enough to have a CCTV magnifier in your practice, use it early in the consultation to get a rapid estimate of the patient’s optimal magnification level, which will also verify whether they have potential for fluent reading. Set optimal contrast, and get the patient to control the magnification level to find their most comfortable print size, and then start trying optical magnifiers with a similar magnification.

When a patient has been struggling for a long time, it’s a real morale boost when you show them that they still have the potential to read well. On the other hand, if they can’t achieve comfortable fluency at any magnification level even with optimal contrast and brightness on a CCTV, you know they won’t achieve it with an optical magnifier either, which at least spares everyone the frustration of a fruitless search.

READ

LOW VISION: Part 1. Understanding

LOW VISION: Part 2. Illumination

LOW VISION: Part 5. Choosing aids

LOW VISION: Part 6. More about aids

______________________________

This series of articles has been prepared with the support of the Tasmanian Optometric Foundation. Contact Paul Graveson at admin@hobartoptometry.com.au.