1:30min

Professor Helen Swarbrick, left, and Associate Professor Laura Downie, right.

By Helen Carter

Journalist

Newly retired after dedicating her stellar career to vision research, the often nick-named ‘Mother of Orthokeratology’ Professor Helen Swarbrick, and rising clinical research star Associate Professor Laura Downie, also on a path to research glory, are two of the optometry professions’ leading researchers.

They are highly respected in their fields both in Australia and overseas and have received many prestigious awards and honours due to their incredible work ethic and brilliant research minds. They espouse the joys of teaching and educating optometry students but also love research, motivated by the thought of making a discovery that could improve people’s lives.

Helen, who was diagnosed myopic at age nine, spent three and a half decades developing the science to support the myopia-curbing contact lenses, orthokeratology. When she arrived in Australia, an oversupply of graduates meant the young optometrist could only find work as a waitress in a pizza restaurant before being fortunately saved by Brien Holden to work in contact lens research, and the rest is history.

‘My greatest achievement was to introduce science to the field of orthokeratology,’ Professor Swarbrick told Optometry Australia. ‘Ortho-k was not popular and slightly disdained in the early days, but nowadays any optometrist who is serious about using myopia control (and that really should be all optometrists!) needs to learn about orthokeratology as an effective option that can be presented to parents of children with progressing myopia.

‘I was lucky in my timing, as the unique reverse geometry lens design had just been developed, corneal topographers were around to help us understand what we were doing to the cornea, and high Dk RGP lens materials made overnight orthokeratology possible.

‘Also, there were a lot of clinical enthusiasts out there to feed back into my research efforts. A special mention must go to John Mountford and Don Noack, who were integral and essential to my early work in the field.

‘Directly related to this, my proudest achievement was the PhD supervision and development of the next generation of researchers in this field – people like Ahmed Alharbi, Paul Gifford, Pauline Kang, Edward Lum, Jeong Ho Yoon, Vinod Maseedupally, and Rajini Peguda. These young people are my family, and I am immensely proud of them. They will take forward my legacy into the future now that I have retired.’

Professor Swarbrick, second from left, with some of her team

Professor Swarbrick, second from left, with some of her team

Laura Downie

Laura, who was fascinated by science as a child, became a university lecturer in 2013 and a year later had established her own anterior eye, clinical trials and research translation unit at the University of Melbourne. An associate professor by age 37, she has developed many tools to help optometrists with the diagnosis and management of dry eye and age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and is now developing a world first point-of-care dry eye diagnosis and sub-typing device for optometrists to have in their practices.

Her research seeks to deliver tangible improvements in the provision of eye care to people with eye disease.

Associate Professor Downie says: ‘Every day is different and rewarding, and I feel privileged to work in such an inspiring environment with exceptional colleagues, and to be undertaking research that is important to me, my profession and my patients.

‘Throughout my academic career, I have maintained my clinical practice and still consult as an optometrist in a private practice on Saturdays. By practising as a clinician, I can directly see the clinical areas where more knowledge is still needed; this might be in the form of understanding the cause of an eye condition, or needing a new diagnostic or treatment to better care for patients. These insights help inform the direction and priorities for my research program.

‘It is a privilege to be an academic and researcher. I love being able to lead research that has the capacity to make a positive difference to patients’ lives.’

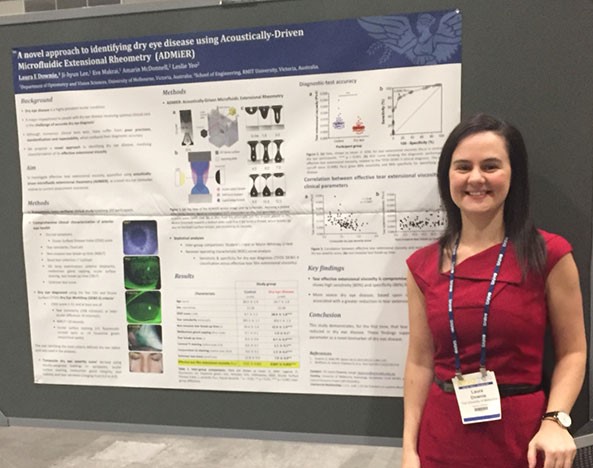

Associate Professor Downie presenting on the dry eye device

Read more of their fascinating stories below:

What made you want to study optometry?

Helen: ‘I was found to be myopic at age nine because of a smart teacher who picked the signs. So, I was aware of optometry as a profession from a young age. When I left high school to go to university my mother got me into contact lenses – only PMMA was available then – and this further piqued my interest. My mother favoured medicine as a career choice for me, while my father preferred engineering – so optometry seemed like a good compromise! And I discovered I would need to leave home to study optometry, a very exciting prospect at age 18!’

Helen, second from left

Laura: ‘My interest in science began early. I remember hand building a crystal radio with my dad and writing messages in ‘invisible ink’ using lemon juice with my mum, in early primary school. When I started learning about science more formally at school, I was fascinated by rainbows and light, and still also vividly remember my year 10 science unit on ‘the eye,’ and learning about its anatomy and the fundamentals of eye-sight and vision.

‘I chose to pursue a career in optometry for several reasons. I have had a long-standing fascination with the eye and vision, and was a high achiever in the maths and sciences throughout school. I also see myself as a ‘people’ person – I empathise with my patients, and really enjoy being able to help them achieve their best vision outcomes.’

Did you practise for a few years? How did you get into research/academia and what made you swap practising for lecturing and researching?

Helen: ‘I practised optometry in a range of practices around Auckland (city, Onehunga, Howick, Papatoetoe) for four years while I completed my MSc degree part-time. I then travelled to the UK and practised as an ophthalmic optician for 2.5 years at a range of practices in and around London.

‘When I first arrived in Sydney in 1980 there were no jobs for optometrists due to an oversupply of graduates. After a frustrating period working as a waitress in a Rose Bay pizza restaurant, I received a phone call from a certain Brien Holden who had heard about me and wanted to offer me a job in the Cornea and Contact Lens Research Unit (CCLRU.) I worked for him in the old Newton Building as a statistician and computer liaison officer, struggling with the large cyber computer in the physics basement, and learning the joys of computer punch-cards.

ROK stars: Helen’s farewell afternoon tea at UNSW’s School of Optometry and Vision Science included members of her original Research in Orthokeratology (ROK) Group

‘After almost three years in the UK and travelling I returned to Sydney at the end of 1983 and started work almost immediately at the CCLRU in its new premises at Randwick. I worked for the CCLRU in several roles in research, including scientific writer and research optometrist, over 11 years.

‘I enjoyed the research world so much that I even took five years off to complete a PhD. After a further short period with the CCLRU/CRCERT (Cooperative Research Centre for Eye Research and Technology) I was keen for new challenges, and applied for a position as a Lecturer at the School of Optometry, UNSW. This introduced me to the joys of teaching and educating young optometry students. I also continued my research interests, but now as an independent researcher.

‘I started at the CCLRU early in 1984, did my PhD from 1986-1992 and moved to the Optometry School in 1995 so although my School academic career was 25 years, I have been involved in research for 36 years!’

Laura: ‘I graduated with a Bachelor of Optometry and Diploma of Music (Practical – Violin) from the University of Melbourne in 2003. In 2004, I commenced my PhD at the same institution, under the supervision of Professor Erica Fletcher, Professor Algis Vingrys and Associate Professor Michael Pianta. My PhD examined the neuronal, vascular and glial cell changes in retinopathy of prematurity, a potentially blinding condition that develops in premature newborns following supplemental oxygen. This work identified, for the first time, that modulating the ocular renin–angiotensin system was retino-protective.

‘After my doctorate, I undertook five years in full-time optometry practice in Melbourne. This time in practice was essential to further my expertise in ocular disease and advanced contact lens fitting, as well as to gain first-hand insight into some of the potential knowledge gaps in practice, which would then benefit from research to improve clinical care.

‘I was inspired to become a researcher as I’m passionate about learning, naturally curious and am motivated by the thought of making a discovery that could really improve people’s lives.

Associate Professor Downie using a slit lamp in the laboratory

‘I commenced my first academic role as Lecturer and Clinical Leader (Cornea and Contact Lenses) in the Department of Optometry and Vision Sciences at the University of Melbourne in 2013. I established my own research unit, the Downie Laboratory: Anterior Eye, Clinical Trials and Research Translation Unit the year after.

‘In 2016, I was promoted to Senior Lecturer and I am now an Associate Professor and inaugural 2020 Dame Kate Campbell Fellow at the University of Melbourne. In this role, I provide didactic and clinical training to Doctor of Optometry students, lead the specialty Cornea clinic at the Melbourne Eye Clinic and direct a wonderful 11-member research team, comprising six PhD and one Masters students, and four research staff.’

What are your major research interests and why did you choose them?

Helen: ‘When I left the CCLRU for the School in 1995, I needed to establish an active research area. The obvious choice was in contact lenses, where I had focussed my interest over the previous 11 years. But the CCLRU was a big world-famous research group, so how could I distinguish myself from them and establish my independent profile? I chose deliberately to work in the area of rigid contact lenses, something that the CCLRU/CRCERT was not particularly interested in at the time, and I was a rigid lens wearer myself.

‘My then Head of School, Daniel O’Leary, attended a conference in the US and returned with a trial set of the old Contex OK-4 lenses. Together with a student from Hong Kong, Gunter Wong, we decided to see if these lenses worked. The outcome of that research project was published in Optometry and Vision Science in 1998, and was the start of my research career in orthokeratology. In that paper we presented a novel explanation for the corneal shape change (and myopic refraction correction) induced by orthokeratology lenses – not corneal bending but central corneal epithelial thinning. The path forward for me was now clear.’

Laura: ‘My research has three main foci: –

Anterior eye biomarkers of disease which focusses on using tears as a platform for understanding disease, across a spectrum of health conditions, ranging from dry eye disease, through to diabetes and infectious disease.

Clinical trials: this body of work has supported the translation of new therapies into clinical practice including regulatory approval of two dry eye therapies in the US and Canada with over 21 million units of these therapies sold since market release in 2017.

Research translation: this area focuses on evidence synthesis (including systematic reviews and meta-analyses) and implementation science. This research provides the basis for developing new interventions to enhance the delivery of eye care, to improve patient outcomes across multiple areas of practice, particularly AMD.

‘One influential moment which inspired me to follow a career in eye research was during my optometry training, where we visited Vision Australia and were blinded-folded for an hour to appreciate for a small period, the profound effect of vision loss. I remember the difficulty in performing even the simplest tasks and thinking to myself how challenging it would be to be significantly vision impaired. This experience led me to consider how I could contribute to furthering scientific understanding about blindness and eye disease, and was one of the factors that inspired me to consider pursuing a doctoral degree in retinal disease.’

Laura, third from left, and senior lecturer Dr Holly Chinnery, fourth from left, work closely together and co-supervise several PhD students. Their combined laboratory teams are called the Front-Tear lab

Laura, where is your point of care dry eye technology at? When are you expecting it on the market? Will it be a game changer, helping diagnose more patients earlier and mean better treatment?

Laura: ‘Accurate and early diagnosis of dry eye disease is currently a clinical challenge as many of the current tests are invasive, time-consuming and inaccurate. Dry eye affects about 20 per cent of adults and is the most common indication for medical eye care in developed countries.

‘Dry eye compromises the tear film and ocular surface, which can lead to eye pain, impaired vision and reduced quality-of-life. Clinicians can now access a range of therapies but need to know which to use and when to use them. It is of critical importance to determine the subtype (i.e. evaporative or aqueous-deficient dry eye) as this informs treatment decisions. But currently there is no single method to both diagnose and subtype dry eye disease.

‘Our answer to these clinical needs is ADMiER (Acoustically Driven Microfluidic Extensional Rheometry) which we are developing as a point-of-care test for rapid and accurate dry eye diagnosis and subtyping. ADMiER involves analysing the stretching properties of a tear droplet to diagnose and subtype dry eye. I am leading this project, in collaboration with Professor Leslie Yeo and Dr Amarin McDonnell from RMIT University to develop ADMiER as a novel point-of-care device.

‘We have built a research-grade prototype, secured a strong patent portfolio, and published a clinical dataset that demonstrates proof-of-concept for ADMiER’s diagnostic utility. This research was published in Ophthalmology and last year I presented on the technology at several scientific meetings including the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO) and International Ocular Surface Society meeting, both in Vancouver, and Accelerating Australia Life Sciences Innovation Showcase and World Congress of Inflammation, both in Sydney.

‘We were also awarded a 2020 NHMRC Development grant to support further development of the technology. This next stage focuses on clinical validation of the device, and developing and optimising a next-generation prototype. We are working towards the product being available on the market in the next five years.’

Laura, you also do research in AMD…what have you done in the past and what are you currently working on?

Laura: ‘The major focus of my AMD research has been to improve the translation of research evidence into practice to support delivery of the highest quality patient care.

‘In 2015, I became the first optometrist to be awarded an NHMRC Translating Research Into Practice (TRIP) Fellowship. The project, entitled “An integrated approach to improving the primary clinical care of patients with early stages of age-related macular degeneration,” involved a multi-dimensional approach to improving the translation of evidence into clinical care provided to AMD patients by optometrists. Significant project achievements included:

- i) development and validation of new tools (a tobacco smoking and diet/nutritional supplement tool) to assist optometrists in assessing these key modifiable AMD risk factors. These are the first clinical tools of their kind to have been developed for primary care practice;

- ii) dissemination of the tools to the profession through continuing education conferences, scientific meetings, workshops, webinars and education articles;

iii) creation and dissemination of an AMD Integrated Care Pathway (ICP), to enhance the efficiency and efficacy of clinical care. The AMD ICP is based on a systematic literature review and provides criteria regarding best-practice AMD diagnosis, management and treatment;

- iv) establishing and leading an AMD Clinical Teaching and Demonstration Service at the University of Melbourne, as a model for primary care excellence. Over one year, Victorian optometrists accompanied their patients for guided best practice care, delivered by my TRIP project mentor, Associate Professor Peter Keller and myself. The AMD service, being unique in scope and operation, provided a patient care service, resource centre and working model for evidence-based AMD care for about 30 optometrists who engaged in the program.

‘With funding from a 2015 Macular Disease Foundation Australia grant, I also led a project to develop a novel optometric clinical audit tool (the Macular Degeneration Clinical Care Audit Tool: MaD-CCAT), to enable optometrists to assess the quality of eye care they provide to AMD patients. This was accompanied by a national education program to upskill practitioners on contemporary research evidence relating to AMD clinical diagnosis and evidence-based management. One of my Masters students, Sena Gocuk, is currently using the MaD-CCAT to evaluate efficacy of in-office digital and paper-based clinical tools for providing care to AMD patients.

‘Collectively, this work has sought to deliver immediate, tangible improvements in the provision of eye care to AMD patients in Australia.’

Professor Swarbrick speaking at a conference

What excites you about research and academia?

Helen: ‘Discovering new things! Changing the conventional paradigm! In the process, helping patients and the profession by keeping the discoveries clinical and relevant.’

Laura: ‘It is a privilege to be an academic and researcher. I love being able to lead research that has the capacity to make a positive difference to patients’ lives. My research is highly interdisciplinary, and so I have the unique opportunity to collaborate with many talented individuals from disciplines including engineering, immunology, neuroscience, neurology, ophthalmology and endocrinology. We come together to create innovative solutions to clinical challenges.

‘Another really enjoyable part of my role as an academic is sharing my research with others at scientific conferences, clinical education meetings, as part of my teaching, and even when providing care to my patients. Being an academic also provides many opportunities for international travel, which I enjoy.’

What excites you about lecturing and teaching – do you love explaining things to students and seeing the light bulbs go on and triggering that passion in them for learning and researching?

Helen: ‘Yes, all of the above.’

Laura: ‘Teaching is an extremely rewarding part of my role at the university. I have always enjoyed teaching and mentoring, ever since I began teaching my first violin student, when I was 17. It is a privilege to be able to contribute to training the next generation of eye care clinicians and researchers. It is rewarding to see your students’ skills develop and to know you have been a part of their educational journey. I am very proud of my students’ accomplishments, and take pleasure in acknowledging and celebrating their successes.’

Laura, centre left, and senior lecturer Dr Holly Chinnery, centre right, are pictured with their combined laboratory teams, the Front-Tear lab

Would you encourage other female optometrists to go down this path, and if so why?

Helen: ‘Of course. Why? It is so much fun!’

Laura: ‘Yes, I would encourage other female optometrists to pursue a career in academia. Many institutions have specifically recognised the importance of encouraging women to pursue academic careers, and to support them to progress and advance in their careers. I love my job and the many opportunities it affords.’

Have there been any challenges as a female in research/academia, and if so, how have you overcome them, or do you think that nowadays females are equally as accepted in this field and have the same opportunities as males?

Helen: ‘I have been pretty lucky, mainly because of the great support I have had from (mainly male) colleagues. I also got very involved in the university politics of gender equity during the early 2000s, and my profile in this area has helped me to deal with the usual challenges of working in a male world.’

UNSW School of Optometry and Vision Science colleagues who, with Helen, recently contributed chapters to a contact lens book

Looking back on your career, what tips could you give other women entering the research/academia field?

Helen: ‘One of the most important things is to find a good mentor – someone you can bounce ideas off, and someone to give you support and guidance. It is also good if this person (or persons) is also in your field so they can introduce you to other academics and researchers to help you build your networks and your profile.

‘In the early days it is important to persist and keep trying. As a young academic there are some very tough times and lots of knockbacks, particularly in terms of gaining funding for your research. Don’t lose heart and keep trying.

‘As a new researcher, you need to get your name out there. Attending conferences is a really important way to connect with others in your field. Early in my independent career I used my own money to fund travel to important overseas conferences and it paid off over time. Also, start to publish papers. They don’t have to be in the big journals at first (although this is a plus!), but building a publication record is essential to move your career forward. Kickstart this by supervising student projects (undergraduate/honours/Masters/PhD) and they will do the work so that you can present at conferences and publish in collaboration.’

Develop a unique research field or topic

Professor Swarbrick has these final words for aspiring researchers:

‘Try to develop your unique research field or topic. Although early collaborations are important to get you going, what will really help your long-term career is to be known for something different that will be associated specifically with your name. ‘For me, this unique area was orthokeratology – not popular and slightly disdained in the early days, but I used this to build my name and my successful research career.’

When you started were there many female optometrists in research and academia or were you a trailblazer? Who were your heroes?

Helen: ‘When I started studying optometry at the University of Auckland in the early 1970s there were very few women in optometry – the wonderful Peg Woods was one of few pioneers. But in our year, out of 15 students four were women. This caused some consternation in the profession at the time. How things have changed!

‘When I started research at the CCLRU, almost all of my colleagues in the research group were women! Brien Holden was good at selecting talent and most of it was female in those early days. Names like Debbie Sweeney, Tailoi Chan, Donna La Hood, Michele Madigan are still well known in the field. In terms of female researchers from other institutions, there were few but some standouts were Suzi Fleiszig, Erica Fletcher and Fiona Stapleton (who did their PhDs at the same time as me). Karla Zadnik from the US is also one of my heroes.’

Laura: ‘There are many outstanding women academics in optometry who have inspired me, and continue to inspire me! Just a few of these people who have particularly had an influence in my career to date are: Erica Fletcher (my PhD supervisor and mentor), Allison McKendrick (our first female Head of Department at the University of Melbourne) and Suzi Fleiszig (Professor at UC Berkeley).

Helen receiving applause at her farewell afternoon tea with UNSW staff

With the myopia epidemic, is ortho-k something more optometrists should adopt and recommend?

Helen: ‘Orthokeratology has an important role to play in myopia control although many other options are becoming available in both optical and pharmaceutical modalities. Any optometrist who is serious about using myopia control needs to learn about orthokeratology as an effective option that can be presented to parents of children with progressing myopia.

‘Children seem to adapt quickly to this overnight lens-wearing modality, which also has the major advantage of device-free clear vision during waking hours. It is an ideal modality for correction of myopia in active outdoors children during the day, and nightly lens wear is under the supervision of the parents.’

How have you balanced work and life?

Helen: ‘With the help of my favourite red medicine and a joyous bunch of crazy friends at the local pub. I also have the affection of two elderly cats who keep me sane!’

Silver and Freddy

INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S DAY COCKTAILS AND SPEAKERS EVENT

To celebrate International Women’s Day , Optometry Australia’s inaugural Cocktails and Conversations event will be tomorrow, Wednesday March 11. The evening will focus on exploring the impact of gender in the optometry profession and opportunities our profession provides for women to foster fulfilling and rewarding careers within and outside of practice.

Hear from Tasneem Chopra and Optometry Australia Director and former Deputy President Kylie Harris before being invited to share your thoughts and experiences. Members in Melbourne – join us at a face-to-face event with beverages and canapes provided. The Melbourne event will be live with presentations live-streamed to anyone who wants to arrange their own event. To arrange a live-stream email policy@optometry.org.au.

- Melbourne: 7pm to 9pm March 11 at The Craft and Co – 390 Smith St, Collingwood Register here

Tagged as: AMD, Dry eye, Myopia, Patient management, Universities