1:30min

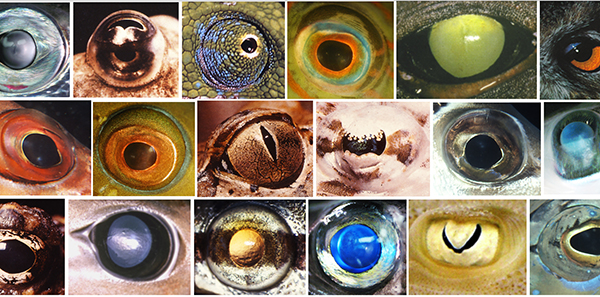

Vertebrate eyes

______________________________

By Rhiannon Riches

Assistant Editor

Vision scientist Professor Shaun Collin has forged a distinguished and exciting research career by integrating the fields of neuroscience and marine science.

For his contribution to research, Optometry Australia has awarded the 2016 H Barry Collin Research Medal to Professor Shaun Collin, who is from the School of Biological Sciences and the Oceans Institute at The University of Western Australia (UWA).

During his Bachelors, Honours and Masters degrees in science at The University of Melbourne, Shaun Collin developed a keen interest in neurobiology, working on the integration of sensory input in the central nervous system of insects in addition to being trained as a marine zoologist. His training fuelled his passion for understanding how animals interpret sensory information and how this is manifest in different behaviours.

Shaun Collin then worked as a Research Assistant at the National Vision Research Institute (NVRI) in Melbourne, studying eye movements in birds with Professor Ian Bailey before moving to Sydney to work with Professor David Sandeman at The University of New South Wales, where he investigated the eyes of fiddler crabs and how they perceive their panoramic environment.

In 1983, he entered the corporate world, becoming a technical representative for a large pharmaceutical company. Despite being awarded the marketing prize for Australia and New Zealand that year, Shaun Collin wanted to return to a career in research and undertake a PhD.

Professor Jack Pettigrew, who was to be awarded the H Barry Collin Research Medal in 2010, had an enormous influence on Shaun at this stage in his career. Knowing of Shaun’s interest in both marine science and sensory neurobiology, Professor Pettigrew suggested to Shaun that he work on the visual system of fishes at The University of Queensland for his PhD.

After visiting the university’s marine station on Heron Island on the Great Barrier Reef, Shaun was hooked and took up an FG Meade Memorial Scholarship in Physiology with Professor Pettigrew as his supervisor.

Postdoctoral positions

Following a successful PhD, Shaun was offered a string of postdoctoral positions at the NVRI (with Professor David Vaney), The University of Montreal (with Professor Babu Ali), The University of California San Diego at Scripps Institution of Oceanography (with Professor R Glenn Northcutt), The University of Washington at Friday Habor (with Professor David Bodznick), the Marine Biology Laboratory in Woods Hole, The University of Tuebingen in Germany (with Professor Hans-Joachim Wagner) and The University of Western Australia (UWA) (with Professor Lyn Beazley), where he held a series of prestigious fellowships including a Fulbright Fellowship, an NH&MRC CJ Martin Fellowship, an ARC QEII Fellowship and an Alexander von Humboldt Fellowship.

‘I went to Germany for a year and a half on a Humboldt Fellowship to study the visual systems of deep-sea fishes … in a landlocked country,’ he said. ‘I took part in a number of deep sea expeditions, spending months at sea. We dropped nets that took six hours to resurface from depths of up to six kilometres, bringing fish to the surface. This provided a wealth of samples to work on in Germany.

‘Travelling abroad to conduct research is both exciting and important for developing as a scientist and a person,’ he said. ‘I have been fortunate to be able to reveal many of the amazing visual adaptations of many different animals, especially those in Australia.’

During this period of over 10 years, Shaun completed studies on visual adaptations in the eyes of ice fishes, comparative studies of corneal projections, the development of retinal projections in fishes, sensory integration in the central nervous system of sharks, visual adaptations of deep-sea fishes to perceive bioluminescence; topographic variations in retinal cell density in the eyes of a range of fishes, birds and mammals from different environments; comparative optics, ocular anatomy, the evolution of colour vision and the electrophysiological mapping of visual input in cartilaginous fishes.

In 1999, Shaun moved to The University of Queensland to take up a permanent position within the Department of Anatomical Sciences, which later merged with a number of other departments to become the School of Biomedical Sciences. This tenured position enabled him to be promoted to full Professor, where he led an active research program within the Sensory Neurobiology Group (formerly the Vision, Touch and Hearing Research Centre), while fulfilling his large teaching and service responsibilities.

Professor Shaun Collin

Although Shaun was finally appointed Head of the School of Biomedical Sciences, he was tempted westward by an offer which he says he could not refuse.

Neuroecology Group

In late 2009, Shaun returned to UWA to take up a prestigious WA Premiers Fellowship to work on ‘The evolution of light detection: eco-physiological impacts on biodiversity, sustainability and health’. He formed the Neuroecology Group, which has forged links with more than 240 collaborators worldwide and created a supportive intellectual environment for postgraduate training.

At UWA, he is a Winthrop Professor, where his research centres on using a range of vertebrate models to investigate their sensory systems (vision, olfaction, audition and electroreception) in the context of evolution, development and plasticity. He is also the deputy director of the Oceans Institute at UWA.

Dedicated to investigating the neural basis of behaviour in a range of vertebrates with a particular focus on sharks, he uses a range of techniques including anatomical, electrophysiological, molecular and bioimaging approaches.

He considers collaboration to be a wonderful and fulfilling part of his research career. His work with colleagues has included a recently published paper on vision in crocodiles, a comparison of differences in retinal anatomy between left and right eyes in cockatoos, and a study on retinal ganglion cell topography in the eyes in giraffes and their adaptations for viewing their world from an elevated position.

Shark deterrents

Over the past three years, Professor Collin has been funded by the Western Australian Government to develop and test shark deterrents based on his knowledge of the sensory systems of sharks and their relatives. Based on his Neuroecology Group’s discovery of colour blindness in sharks, shark deterrent wetsuits have been developed and novel repellents tested based on using bubbles, lights, electric fields and sound to change shark behaviour. His multidisciplinary approach has enabled him to partner with numerous industries.

‘Only some marine animals have the ability to detect electric fields; sharks are one of them. Oddly, platypus and echidnas can too,’ he said. ‘There was very little known about the shark’s visual systems when I started. We investigated how they navigate through their environment and perceive prey. Eyes differ in each species of shark depending on their habitat, for example whether they live in shallow water or the deep sea.

‘In a nutshell, animals’ eyes are similar to the human eye but I’m interested in what is different, depending on the visual demands of each species and the ambient light conditions. For fishes and sharks, their eyes can change and adapt throughout their life. The eyes show a level of plasticity, changing during development.

‘Another point of difference between sharks and most other animals is that they are colour blind. They see in shades of grey. This was discovered when we were working on the evolution of colour vision in the animal kingdom. We discovered that the representatives of the earliest stage in vertebrate evolution, the lampreys, have the most elaborate colour vision system but this ability has been lost in the sharks,’ Professor Collin said.

The Western Australian Government has also funded a number of studies to test existing shark deterrents as most devices on the market have not been tested.

‘We received three major grants. One of these was to test existing deterrents such as the shark shield, an electronic device that divers tie around their ankle. We tested these on Great Whites in South Africa and this paper has been published.

‘Another grant was to test whether sharks attack people by mistake. We have measured the visual, auditory and electromagnetic cues that are produced by both humans and typical shark prey (seals). We wanted to compare these signals and negate any similarities that may guide a shark to attack a human by mistake by masking. This is the subject of ongoing research,’ he said.

Professor Shaun Collin will be presented with the H Barry Collin Research Medal in 2017.

‘I am honoured and humbled to receive the award created in honour of my father’s contribution to optometry and vision science 40 years earlier,’ he said. ‘I am a third-generation vision scientist, with my father and grandfather both being optometrists.

‘I hope to share more of our work through Clinical and Experimental Optometry and to present our research findings to optometrists at one of their conferences,’ Professor Collin said.