1:30min

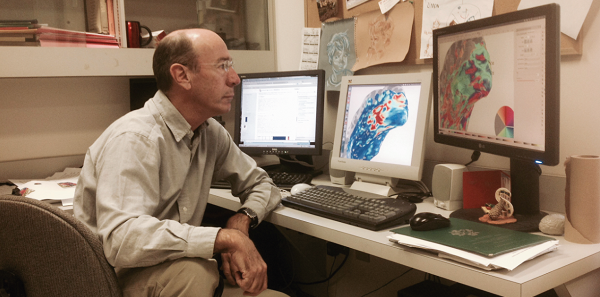

Robert Hess’s curiosity about optometry has led to him being awarded the 2013 H Barry Collin Research Medal.

Professor Hess, director of research in the Department of Ophthalmology at McGill University in Canada, will be presented with the medal and give an acceptance lecture at the Southern Regional Congress in Melbourne on 1-3 March 2014.

Professor Hess is a world leader in amblyopia. He has been conducting trials to treat amblyopia in adults and children, comparing a monocular approach—wearing an eye patch over the ‘good’ eye—with a dichoptic approach, while playing video games.

The study involving 18 adults with amblyopia, some of whom were patched as children, was published in Current Biology in April 2013.

Nine played videogames for one hour a day while wearing a patch, the monocular approach, and the other nine did so unpatched, playing the same game that was presented dichoptically so that the game information was divided in a complementary fashion between the two eyes. After two weeks the groups swapped.

Professor Hess’s results confirmed the accepted notion that patching of the ‘good’ eye in patients older than 10 years is not effective.

Playing videogames created conditions under which both eyes work together. He found dichoptic training resulted in significantly greater learning effects than monocular training, greater improvements in stereopsis and greater reductions in suppression.

‘… the suppression has been eliminated, binocular vision restored—in the majority of cases improved stereo—and the vision in the amblyopic eye improved,’ Professor Hess said.

The H Barry Collin Research Medal is awarded by Optometrists Association Australia to recognise Australians or persons with a significant connection to Australia, who have made important contributions to knowledge in optics, vision science or optometry.

Tasmanian born and University of Melbourne educated researcher Professor Donald Mitchell was presented with the 2012 H Barry Collin Research Medal award at the Australian Vision Convention on the Gold Coast in April 2013.

Rhiannon Riches talks to Robert Hess about his work

Who or what inspires your research?

I was calibrated, so to speak, in terms of what I consider ‘good’ research by a number of people: Neville Drasdo, Ed Howell and my Cambridge colleagues.

Your interests in optometry and ophthalmology are varied.

I have wide interests. I have done work on audition, normal vision, abnormal vision, human and animals. If the question is interesting, it is worth answering, though sometimes new techniques have to be acquired before this becomes possible.

Have you ever experienced a ‘light-bulb’ moment during your research?

Usually we are so busy in what we do, we don’t have any time to think. When was the last time you sat down for say, half an hour, uninterrupted and carefully thought out a particular problem? Sometimes, it happens when you are jetlagged and you wake up in the middle of the night in some foreign location.

Those times can be really productive. I like to go on regular long-distance runs, during which time I am uninterrupted and free to think about a particular issue. I find most of my ideas come during such times. Funnily enough, you usually realise you have the solution before you consciously know what the solution is.

Have you made any accidental discoveries?

Almost all discoveries are accidental because we know so little. The trick is to know that when you get the ‘wrong’ answer to an experiment with an expected outcome, it may in fact be the right outcome.

What do you consider to be your most valuable contribution to optometry?

I would like to think that I have been able to infect others who have worked with me with the same enthusiasm for research and that they will go on to do great things.

You are visiting Australia in March next year to speak at SRC. What will your lecture be about?

For the past 200 years or so, our approach to the treatment of amblyopia hasn’t changed much. It has not been terribly successful in children and completely unsuccessful in adults. I have recently developed a new approach which I hope will work better in children and which I know will work well in adults. I am hoping optometrists will have an open mind to change.

You’ve studied and worked in Brisbane, Birmingham, Melbourne, Cambridge, Montreal. What led you there?

I started in Brisbane at the Queensland Institute of Technology, as it was then known, where I studied optometry. I liked it but wanted to work in research. I’m not sure why; maybe I had too many questions that the folks at the institute couldn’t answer, or maybe they were unanswerable.

I then did an MSc at Aston University in Birmingham. I met a chap called Neville Drasdo. He impressed me and challenged me; I couldn’t get enough of it. I worked on photosensitive epilepsy. Then I did a PhD at the University of Melbourne and came across a chap called Ed Howell; the same thing happened … I felt challenged … I couldn’t get enough.

Ed was fired up after coming back from a year in Cambridge where people like Fergus Campbell, Horace Barlow and Francis Crick who jointly won the 1962 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, and Alan Hodgkin, jointly awarded the Nobel in 1963, were colleagues.

I then went to Cambridge to do postdoctoral research, expecting to stay for 12 months and ended up there for 13 years, obtaining a faculty position in the Physiological laboratory.

Then I got the opportunity of setting up a Vision Research Centre at McGill University in Montreal, where I am now.